The Real Story

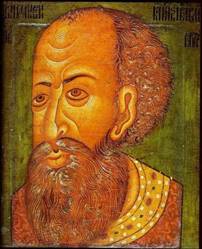

Murder in the Queen's Wardrobe is fiction, but the story of Lady Mary Hastings and

the proposal that she marry Ivan the Terrible is not.

There is

no portrait of Mary, but here is a contemporary likeness of Ivan.

Aside from his reputation for irrational violence, the

other strike against him was that he already had a wife. Actually, he had two,

having put one of them away in a convent in order to wed the other. He is said

to have been deeply in love with his first wife, and devastated when she died.

After that, his matrimonial record is worse than that of Henry the Eighth.

MARY HASTINGS was the youngest daughter of Francis Hastings, 2nd earl

of Huntingdon (1514-June 20, 1561) and Katherine Pole (d. September 23, 1576).

In 1562, Mary's brother contracted a marriage for one of his sisters, either

Lady Elizabeth or Lady Mary, to Lord Bulbeck, the earl of Oxford's heir. The

agreement provided for a dowry of 1000 marks and a jointure of 1000 pounds.

Edward de Vere was supposed to marry one of the sisters within a month of his

eighteenth birthday. Before that date, however, the earl of Oxford died and the

new earl became the ward of William Cecil, Lord Bughley. He married Burghley's

daughter, Ann Cecil, instead. Lady Mary, still unmarried and in her late

twenties, may have been at the court of Queen Elizabeth in 1581 when Dr. Robert

Jacobi, an English physician living in Muscovy, suggested her name to Ivan the

Terrible in reponse to his interest in beginning

negotiations for an English bride of royal blood. Mary qualified, being a

Plantagenet descendent distantly related to the queen. It is uncertain when she

was told of her role in the matter, but if she knew anything about Ivan, she

cannot have been enthusiastic. He was at that time married to his seventh wife,

a woman he planned to discard if the match with an English "princess"

could be arranged. Ivan sent an ambassador,Theodor Andreevich Pissemsky, to

England to negotiate the marriage and an alliance against the king of Poland.

He was to report on the height, complexion, and measurements of the proposed

bride and procure a portrait of her. Ivan was looking for a stately appearance,

and would also require that Mary and all her attendants convert to the Orthodox

religion. Queen Elizabeth, who wanted exclusive English access to the port of

St. Nicholas, deliberately delayed committing herself with the ambassador, who

arrived in England in September 1582, at first telling him that Mary had

recently had smallpox and that a face-to-face meeting and a portrait would be

intrusive. In May 1583, however, she could put him off no longer. There are

several contradictory accounts of the meeting, based on a report by the

ambassador himself (translated) and a memoir by Sir Jerome Horsey, who was not

present. They differ widely in some areas but agree that the meeting was in the

Lord Chancellor's garden. The Lord Chancellor was Sir Thomas Bromley, but while

the ambassador's account says the garden was at Bromley's country house, Horsey

places it in the gardens at York House, near Charing Cross in the city of

Westminster. According to the ambassador, he did not actually speak to Lady

Mary. There was a party of ladies in the garden and Lady Mary was pointed out

to him. She was walking at the head of the group, between the countess of

Huntingdon (her brother's wife, born Katherine Dudley) and Lady Bromley

(Elizabeth Fortescue). The two groups circled the garden several times, passing

each other, so that the ambassador could get a good look. Horsey's version, in

which the ambassador throws himself on the ground before the tsar's betrothed

and declares she has the face of an angel, seems unlikely. What the ambassador

did say was, "It is enough." He reported to the tsar that "The

Princess of Hountinski, Mary Hantis

is tall, slight, and white-skinned; she has blue eyes, fair hair, a straight

nose, and her fingers are long and taper." Some translations make her eyes

grey. The long-awaited portrait was completed in time for him to take it with

him when he returned to Russia. He embarked on June 22, 1583 along with

England's new ambassador to Russia, Sir Jerome Bowes. Bowes's instructions were

to dissuade the tsar on grounds of Mary's poor health, scarred complexion, and

reluctance to leave her friends. Until Ivan's death on March 18, 1584, Mary (at

least according to Horsey) had to put up with being called "the Empress of

Muscovia." Mary herself died, still unwed,

before 1589, by which date a bequest in her will was being contested. One

source says her death came shortly after a visit to her brother in Ireland but,

so far, I've found no record that any of her brothers was serving there in the

1580s.

Two

other real people who play a role in Murder

in the Queen's Wardrobe are the ambassadors, Theodor Andreevich Pissemsky (various spellings) was sent to England by Ivan

the Terrible in 1582. Below is a painting showing Queen Elizabeth giving an

audience to foreign ambassadors. It is doubtful it portrays the Russian, but he

would have been received in a similar setting.

Sir

Jerome Bowes was sent as Ambassador to Russia in 1583. He was not a great

success. We do have a portrait of him.

Similarly,

Sir Francis Walsingham, Sir Thomas Bromley, George Barne, Dr. Robert Jacobi, Prince

Albertus Laski, and Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester are all real people. Below

are portraits of Walsingham and Leicester.

There

are other real women in the novel, as well.

KATHERINE DUDLEY was the

daughter of John Dudley, duke of Northumberland (1504-x.August 22, 1553) and

Jane Guildford (1509-January 15, 1555). Although the Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography gives her birthdate as c.1538, there is a record of a

christening on November 30, 1545 that several authorities believe was

Katherine's. The godparents were Francis van der Delft, Imperial Ambassador to

England, Princess Mary, and Catherine Willoughby, duchess of Suffolk, who

hosted a reception at Suffolk Place, Southwark. Assuming this birthdate to be

correct, Katherine was seven when she was married to eighteen-year-old Henry

Hastings (1535-December 14, 1594) on May 24, 1553 at Durham House in the

Strand. Three months later, her father was arrested and executed for treason.

It would have been easy for her father-in-law, the earl of Huntingdon, to have

her marriage annulled. Instead he took her to Ashby-de-la-Zouche to be raised

with his own family. From 1555 on, under the terms of her mother's will, her

brother Robert paid her a stipend of twenty marks a year. She set up

housekeeping with her husband in 1560. She first came to court in 1562 or 1563

and because her brother, Robert Dudley, was the queen's favorite, she was made

a lady of the privy chamber. In 1564, however, when a book on the succession

urged acceptance of her husband's claim to the throne, Katherine was given

"a privy nippe" by the queen. His assurance

that the book was "foolishly written" did not mend the rift and for a

time Katherine left the court. In 1566, according to an essay by Simon Adams in

Leicester and the Court, the earl of

Leicester's visit to the West Midlands was put off due to the illness "or

possible miscarriage" of his sister, the countess of Huntingdon. In

January 1570, Leicester and both his sisters went to meet their brother the

earl of Warwick at Kenilworth. In 1576, Katherine and her husband became legal

guardians of the earl of Essex's children. She was already fostering and

training several young gentlewomen but had no children of her own. In 1583, she

was in London with her sister-in-law, Lady Mary Hastings, who was under

consideration as a bride for Ivan the Terrible. On June 18, 1584, Katherine was

living in her husband's house in Leicester when her brother, the earl of

Leicester, stopped there for the night on his way back from a visit to the

baths at Buxton. He left at 5 AM the next morning. Katherine spent some time in

the north where Huntingdon was president of the Council of the North, but had

been ill and remained at Whitehall the last time he went to York. She was

prostrate with grief when told of his death. Nevertheless, she returned to

court and was considered one of the queen's closest friends during the last

years of her reign. During the reign of James I, she took charge of the small

daughters of her nephew, Robert Sidney, while he and his wife were in the

Netherlands. She died at Chelsea and was buried there in the parish church.

ELIZABETH FORTESCUE

was the daughter of Sir Adrian Fortescue of Stonor

Park, Oxfordshire (c.1481-x. July 9, 1539) and Anne Rede (c.1510-January 5,

1585). She was married by 1560 to Sir Thomas Bromley (1530-April 12, 1587),

Lord Chancellor of England from April 1579, and was the mother of Sir Henry (d.

May 15, 1615), three other sons, Elizabeth, Anne, Muriel (1560-1630), and Joan

(b.1562). The Bromley children were tutored by William Hergest, who dedicated

his The Right Rule of Christian Chastity (1580) to his charges. It was

in the Lord Chancellor's garden, with Lady Bromley present, that an ambassador

sent by the tsar of Russia was allowed a look at Lady Mary Hastings in May

1583. Lady Mary had been proposed as a possible bride for Ivan the Terrible.

Accounts vary as to whether this garden was at York House, Westminster or at

the Bromleys' country house. Since this was at Holt,

Worcestershire, York House seems more likely. Elizabeth was buried on June 2,

1602 in St. Margaret's, Westminster.

JANE RICHARDS was an Englishwoman living in St. Stephen Walbrook,

London when, on July 18, 1564 she married one Eliseus or Eligius Bomelius (c.1530-1579), also known as Elijah Bomel and Dr.

Elisei. He was a native of Westphalia who had come to England in 1558 to study

medicine at Cambridge. His sponsor was Katherine Willoughby, duchess of

Suffolk, who had been in exile with her second husband, Richard Bertie during

the reign of Mary Tudor, and had given birth to their son, Peregrine Bertie, in

October 1555 in Wesel. It was Eliseus's father, Henry Bomelius

who baptized Peregrine. Eliseus started a practice in London as a physician and

astronomer, living for a time in 1567 in Lord Lumley's London residence near

Tower Hill and later in the parish of St. Michael-le-Querne,

but he neglected to follow the regulations of the College of Physicians and was

arrested in 1567 for practicing without a license and imprisoned in the Wood

Street Compter. He was still confined at Easter 1570,

but as an "open prisoner" of the king's bench. Jane appealed to Sir

William Cecil, who was already acquainted with her husband, for help and

appeared before the censor's committee of the College of Physicians,

petitioning for his freedom. Having decided that London was no longer

welcoming, Eliseus made arrangements to accompany the departing Russian

ambassador back to what was then known as Muscovy, taking Jane with him. They

arrived late in 1570. There he served Ivan the Terrible as a magician and

physician and held a post in the household of the tsar's son. He cast

horoscopes, concocted poisons, and accumulated a fortune. In 1575, however, he

was caught trying to sneak into Riga (controlled by the tsar's enemies, the

Polish) in disguise. Under torture he admitted to crimes against Muscovy. He

died in prison four years later. Jane, who had been left behind in Moscow in

1575, was not permitted to return to England until Queen Elizabeth interceded

on her behalf in 1583. It is uncertain when she left, but it was certainly no

later than May 1584, when Sir Jerome Bowes, the departing English ambassador,

sailed home. On October 28, 1586, a marriage license was issued for Jane, widow

of Eliseus Bomelius, and Thomas Wennington,

gentleman, of St. Margaret Pattens, London.

The

settings used in Murder in the Queen's

Wardrobe are almost all real places. Willow House is fiction, but it's

location, Bermondsey, is as accurate as I could make it. The village is

famously portrayed in a painting by Joris Hoefnagel.

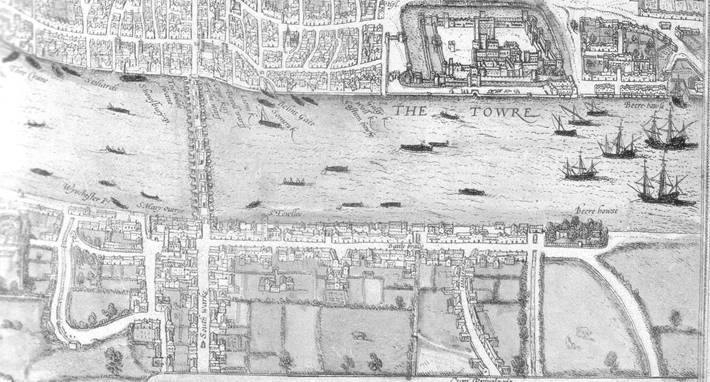

This map

from 1572 also shows the area:

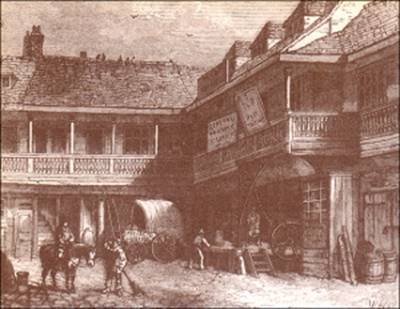

The

Horse's Head Inn is my own invention, but it is based on real inns of the

period. Here's what one of them may have looked like.

Another real place is English House in Moscow, which still exists and is now a

museum. Below are an exterior photo and an exhibit showing an interior scene

from the sixteenth century.